The US is calling for an investigation into the deadly Israeli airstrike on a good convoy in Gaza…Governor Reynolds’ nominee to head the state Education Department is confirmed.

Podcast (news-digest): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The US is calling for an investigation into the deadly Israeli airstrike on a good convoy in Gaza…Governor Reynolds’ nominee to head the state Education Department is confirmed.

Podcast (news-digest): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

A temporary channel has been opened at the Port of Baltimore…the legislature is looking to chance a law that affects Iowans abused by Boy Scout leaders decades ago.

Podcast (news-digest): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Culture Crawl 906 “And The Mighty Wurlitzer, Too!”

The Cedar Rapids Community Orchestra celebrates its 10th anniversary with a special concert April 7 at 3pm in the Paramount Theatre. It will be a bittersweet event, as this will also be director Ghyas Zeidieh’s final concert at the helm.

Ghyas will go out with a bang, though! The program will feature a brand new commission from Cedar Rapids composer Jerry Owen, as well as Ravel’s “Bolero,” and a U.S. premiere from Middle East composer Solhi al-Wadi. The finale will be Saint-Saëns’ Organ Concerto, which will feature the Paramount’s Might Wurlitzer organ!

Admission is free. More information at www.crorchestra.org.

Subscribe to The Culture Crawl at www.kcck.org/culture or search “Culture Crawl” in your favorite podcast player. Listen Live at 10:30am most weekdays on Iowa’s Jazz station. 88.3 FM or www.kcck.org/listen.

Podcast (culturecrawl): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Ethan Johnson, Aaron Piper, and Ash Wasek talk about some of their jazz heroes and play a wide variety of jazz, both old and new during their guest DJ hour.

Ethan, Aaron, and Ash’s playlist:

Podcast (specials): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The regular meeting of the Kirkwood Board of Trustees will take place April 11, 2024. Time, place, and meeting agenda can be found at this link.

Crews continue to work on removing wreckage from the bridge collapse in Baltimore…a new report finds Iowans saying access to contraception has gotten more difficult following the Dobbs decision.

Podcast (news-digest): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Jazz Corner of the World Encore with host Craig Kessler

Jazz Corner of the World Encore with host Craig Kessler

Mondays at 6:00pm

The Brilliance of Bobby Timmons

Craig spins some fine examples of pianist Bobby Timmon’s work on Riverside Records, Prestige Records, and as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

The Wednesday Night Special

Wednesdays at 6:00pm

Vivian Shanley’s Student Gigs

April is Jazz Appreciation Month, when KCCK spotlights the best and brightest student jazz makers. This week, we feature standout gigs from bassist Vivian Shanley at the 2023 Iowa City Jazz Festival and 2022’s Jazz Under the Stars. Vivian is a CR Washington grad, an alum of KCCK’s Middle School Jazz Band Camp, the Corridor Jazz Project, and now a Lawrence University music major and working musician.

Jazz Night in America with host Christian McBride

Jazz Night in America with host Christian McBride

Thursdays at 11:00pm

Betty Carter’s Legacy

Christian McBride celebrates Betty Carter’s lasting influence with a performance by vocalist Charenée Wade at Jazz at Lincoln Center, accompanied by many former members of Carter’s bands through the years.

Jazz Corner of the World with host Craig Kessler

Saturdays from 12 noon to 4:00pm

The Best in Jazz

Join Craig this week as he presents another listen to the best in jazz. Explore the music and its fascinating history.

KCCK’s Midnight CD

Every Night at Midnight

Each night, KCCK lets you hear a new CD played start-to-finish.

Never Felt So Good by Ron Burris on Monday; Live at Jazzcup by Caesar Frazier on Tuesday; Heartland Radio by Remy Le Boeuf’s Assembly of Shadows on Wednesday; Big George by One For All on Thursday; Out of Line by The Wicked Low-Down on Friday; Brick By Brick by JP Soars on Saturday; I Watch You Sleep by Scott Dunn with Claire Martin on Sunday.

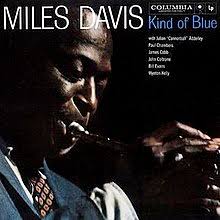

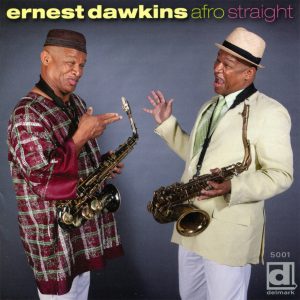

Hey, Jazz fans! Be sure to tune in this week as we celebrate the birthdays of singers Alberta Hunter, Doris Day and Jill Scott, saxmen Harry Carney, Boomie Richman, Stanley Turrentine and Gary Smulyan, pianists Duke Jordan, drummers Stan Levey and Jake Hanna, bassists Scott LaFaro and Chuck Deardorf and more. We’ll also mark the recording anniversaries of Art Pepper’s “The Art of Art Pepper” (1957), Kenny Dorham’s “Una Mas” (1963), Maynard Ferguson’s “Chameleon” (1974), Hank Crawford & Jimmy McGriff’s “On the Blues Side” (1989), Poncho Sanchez’ “Latin Soul” (1999), Ernest Dawkins’ “Afro Straight” (2012) and many others, Mondays thru Fridays at noon on Jazz Masters on Jazz 88.3 KCCK.