Jazz Corner of the World (Encore)

Jazz Corner of the World (Encore)

Mondays at 6:00pm

Sunnyside Records, Part 3

Craig continues his exploration of the top-notch Sunnyside record label, founded in 1982 and operated by Francois Zalacain. We’ll hear a variety of diverse selections from premier jazz artists, such as Gerald Cleaver, Vinicius Cantuaria, Denny Zeitlin, Jamie Baum, Eddie Higgins, Aaron Goldberg, Diego Barber, and a host of others.

Wednesday Night Special

Wednesdays at 6:00pm

Corridor Jazz Project, Night One

KCCK’s Corridor Jazz Project brings together the talented high school jazz bands with the area’s best jazz professionals to rehearse a chart, record it in studio, then perform it live. A record 21 bands took the stage at the Paramount Theatre in Cedar Rapids, and the Voxman Recital Hall in Iowa City.

Jazz Night In America

Jazz Night In America

Thursdays at 11:00pm

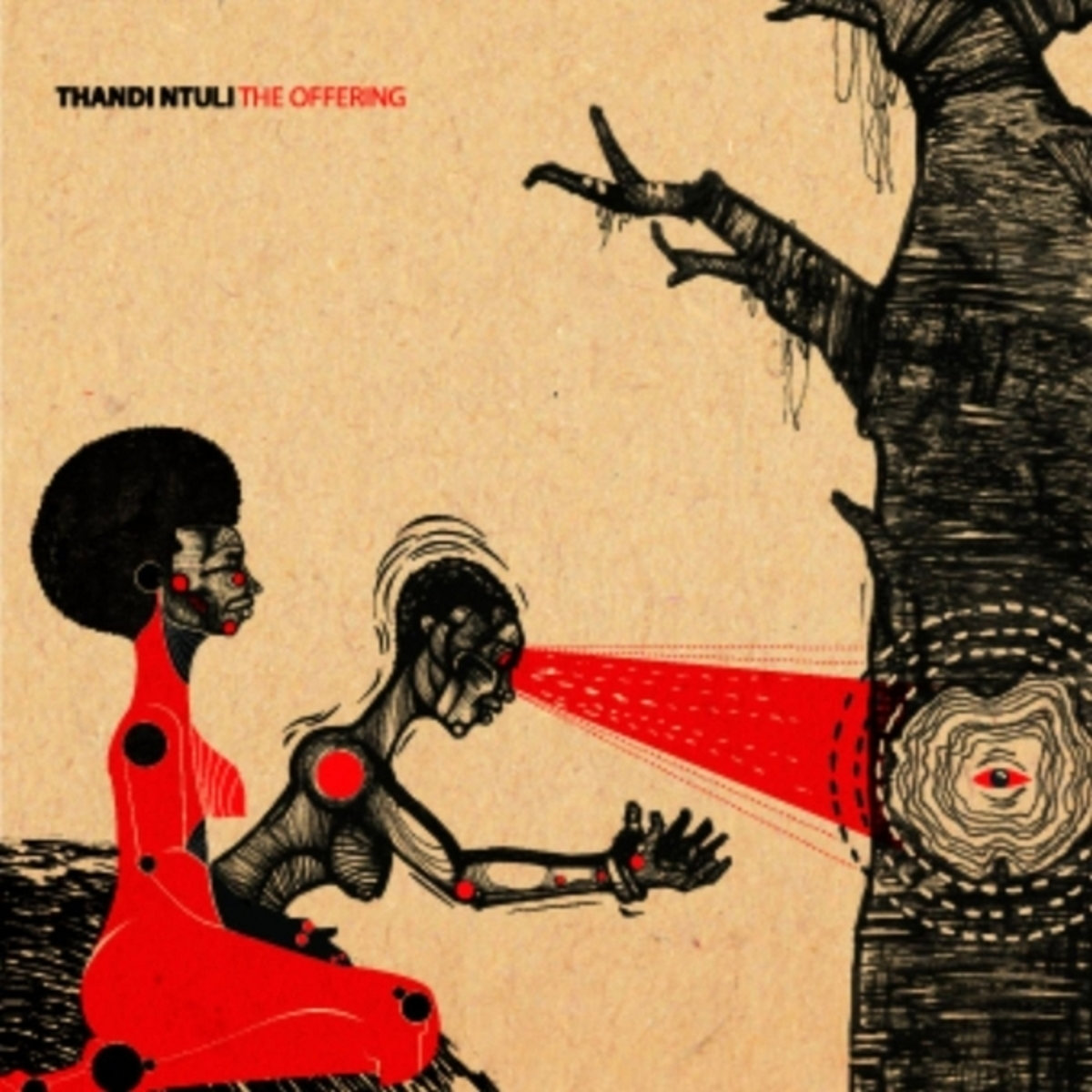

Jazz and Resistance

To celebrate South Africa’s Freedom Day, Christian McBride honors the jazz musicians who stayed and resisted during apartheid — from Winston Mankunku Ngozi to Moses Taiwa Molelekwa — and spotlights pianist Thandi Ntuli, a rising star of the “Born Free” generation.

Jazz Corner of the World

Saturdays from 12:00 noon to 4:00pm

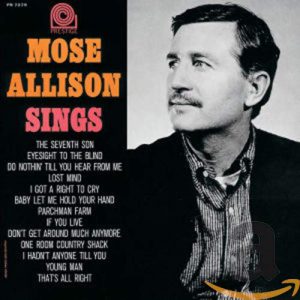

Mose Allison, Part 4

Craig presents his 4th and final chronological spotlight of the superlative artistry of legendary pianist, poet, singer, and composer Mose Allison. In this week’s presentation, we’ll hear selections from his last Blue Note releases, some live dates, and his final recording!

KCCK’s Midnight CD

KCCK features a new album every night, played from start-to-finish.

In Jazz We Trust by the Posi-Tone Swingtet on Monday; The Axes Volume II: Summer Solstice by Daggerboard & the Erik Jekabson Orchestra on Tuesday; Chicago to New York by Eric Alexander on Wednesday; Interaction by 3 Cohens with the WDR Big Band on Thursday; The Speed of Life by Dudley Taft on Friday; Grown in Mississippi by John Primer on Saturday; Back to Brazil by Diane Marino on Sunday.

Born and raised in the vibrant streets of Caracas, Venezuela, Silvano Monasterios is a virtuoso pianist and composer, celebrated for his intricate technique, soulful improvisations, and innovative compositions. Over a career spanning three decades, he’s captivated audiences worldwide, carving a distinctive musical voice that blends harmonic sophistication with fiery Latin rhythms. His new project, “The River,” is a nine-piece ensemble work inspired by the social unrest and protests by the Venezuelan people in 2017 manifested by their desire to live in a free and just place.

Born and raised in the vibrant streets of Caracas, Venezuela, Silvano Monasterios is a virtuoso pianist and composer, celebrated for his intricate technique, soulful improvisations, and innovative compositions. Over a career spanning three decades, he’s captivated audiences worldwide, carving a distinctive musical voice that blends harmonic sophistication with fiery Latin rhythms. His new project, “The River,” is a nine-piece ensemble work inspired by the social unrest and protests by the Venezuelan people in 2017 manifested by their desire to live in a free and just place. For more than twenty years as a recording artist, the pianist and composer Hiromi has shifted seamlessly from one spellbinding project to the next. In the process, she’s earned a reputation as one of the most explosive live performers in jazz history and a global ambassador for the art form. Hiromi’s 13th studio album, “Out There,” is the second release with her band SonicWonder. It features French-born fusion virtuoso Hadrien Feraud on bass, the soulful Chicago drummer Gene Coye, and Brooklyn-raised trumpeter Adam O’Farrill, who is part of a dynasty that includes his father and grandfather, Latin jazz titans Arturo and Chico O’Farrill.

For more than twenty years as a recording artist, the pianist and composer Hiromi has shifted seamlessly from one spellbinding project to the next. In the process, she’s earned a reputation as one of the most explosive live performers in jazz history and a global ambassador for the art form. Hiromi’s 13th studio album, “Out There,” is the second release with her band SonicWonder. It features French-born fusion virtuoso Hadrien Feraud on bass, the soulful Chicago drummer Gene Coye, and Brooklyn-raised trumpeter Adam O’Farrill, who is part of a dynasty that includes his father and grandfather, Latin jazz titans Arturo and Chico O’Farrill.

Hey, Jazz fans! Be sure to tune in this week as we celebrate the birthdays of trumpeter Shorty Rogers, saxmen Gene Ammons and Leo Parker, bassists Richard Davis, Gene Cherico and Buster Williams, guitarist Jeff Golub, flutist Herbie Mann, pianists Pete Malinverni, drummer Danny Gottlieb and more.

Hey, Jazz fans! Be sure to tune in this week as we celebrate the birthdays of trumpeter Shorty Rogers, saxmen Gene Ammons and Leo Parker, bassists Richard Davis, Gene Cherico and Buster Williams, guitarist Jeff Golub, flutist Herbie Mann, pianists Pete Malinverni, drummer Danny Gottlieb and more. Jazz Corner of the World (Encore)

Jazz Corner of the World (Encore)

Jazz Night In America

Jazz Night In America

We’ve had a few repeat guest Djs over the years, but this is the first time an entire team has repeated!

We’ve had a few repeat guest Djs over the years, but this is the first time an entire team has repeated!